March 21, 2017

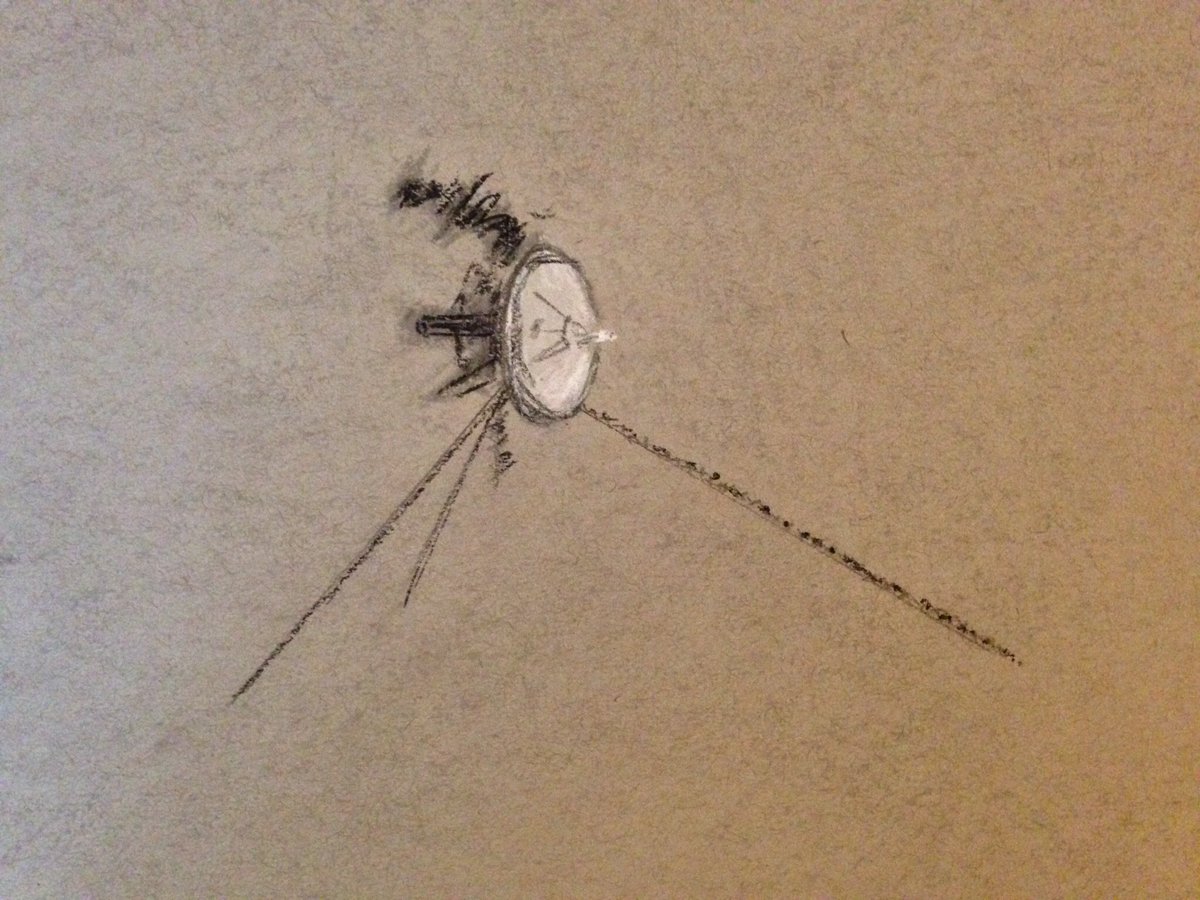

Detect. Transmit.

2017 is the 40th anniversary of the launch of the twin Voyager spacecraft. I found this essay about Voyager on the Internet years ago - I don't remember where and I can't find any breadcrumbs. I'm sharing it, lightly edited, as one of the finest space program essays I've ever found.To imagine what being the Voyager probe would be like, consider the following:

Your life begins, conceived during the mid-60s golden years of the space program.

The core concepts of your design are settled during the first years of that decade, and refined for fifteen years as different attempts are made to extend the reach of man's knowledge first to the skies, then to our nearest neighbors.

Your idea forms in an era of slide-rules and pencils, as astronomical calculations reveal a particularly fortuitous alignment of the outer planets in the coming decade, one that will slingshot you to the outer reaches of the solar system, hopping from planet to planet.

Slowly, your design is solidified, using the best space-worthy technology man has to offer, instrumentation, structure, power, from the peak of each discipline of a nation. The brightest engineers and scientists painstakingly weigh each possible ounce of material with which to construct you, judging the possible benefits that can be attained versus the energy you'll need to accomplish your journey.

After all, the road that you will travel has never before been attempted by this race of surface-dwelling primates, they have the barest idea of what to study.

As the day of your birth approaches, plans are completed, mass and energy budgets are finalized, and your fetus takes form in a sterile clean room. Engineers calibrate your eyes and ears, build each part of your systems from scratch, and then test and re-test until they're as certain as they can be that all of your senses are ready for the trials you will face.

You're folded into the space probe equivalent of the fetal position, your sensors and reactor folded to fit inside the payload compartment of a nearly one and a half million pound rocket fueled by some of the most dangerous compounds known to man. At nearly one thousand times your total mass, this mountain of explosives will catapult you away from the last truly warm place you will ever know, away from the light and heat and activity of your womb, and into the cold blackness that will define you as a success, or perhaps as a failure.

For all the care that has been taken in your construction, if this unstable pillar that provides your birthing contractions were to explode, you would end as just another footnote in a failed attempt to reach into the skies.

-

Fortunately, you are borne into the heavens cleanly; your delivery proceeds exactly as planned, and you begin your travel on the path that was chosen well before your birth.

-

However, your tiny brain, barely a half a megabyte in capacity in today's terms, spread across six different subsystems, gets confused: you are dizzy, disoriented, and lost. Your eyes and ears and heart have all stretched out as they should, and everything is as it was designed to be, and yet you believe yourself lost much further out into the void than you truly are, and you scream the wail of a lost child, long and piercing, unresponsive to any attempt to convince you that you're alright.

A routine in your solid core memory kicks in, and you obey it, and you do the only thing you know. Every part of you shuts down, with the exception of your eye and your tiny legs, the gas thrusters that will help you orient yourself towards the warm light of the sun.

You look around you, and locate this beacon, and as you twist and turn your senses gradually return and you realize that all is well. Finally, you call back home and tell them that all is well, after all. The frantic worrying over your extended silence is over, although you have no way of telling them, or even knowing, what actually went wrong.

You are on your way, and for now they will have to have faith in you.

You are not expected to live much past three years, but your birth is a moment of exultation and relief. You make your way toward your destiny, listening for your creators as you were designed to do, when something happens - or more accurately, nothing.

They are so engrossed in preparing to deliver your twin brother that they neglect you at just the wrong time, and you, hearing nothing, assume that you've gone deaf.

You strain with one ear, then the other, and finally the words you've been awaiting arrive, but the struggle has damaged something vital. One of your ears is now completely deaf, and the other has been damaged irreparably, a million miles from home.

New instructions are sent to you, and you adjust as time goes on, but your hearing will never be quite the same.

And so you wait, almost two long years traveling through the blackness, measuring, sensing, recording all you can detect and sending it back home as a constant yet paltry stream of information, and try not to get too jealous as your twin reaches the first of the outer planets, Jupiter, four months ahead of you.

Yet it will pave the way for your own triumph, for this is the closest anything made by man will have ever, until this time, approached the giant, and its work will help refine what you are to do.

You open your eyes, pitiful in their abilities - a pair of sensors 800 pixels on each side - and every 48 seconds for the next few months, you will repeatedly record what you can see, tell Earth, then repeat, changing filters as you are told to extract as much out of this time as you can.

You help scientists make their careers: between you and your brother, astronomers over 700 million miles away find evidence for volcanism on Io, rings around the planet itself, and are able to study the furious hurricane known as the Great Red Spot in heretofore unthinkable detail.

In approaching the planet, you maneuver so as to steal a tiny bit of its energy to turn into a huge change in course and gain in speed for yourself, sending you barreling off towards the sixth planet, Saturn; and again, you enter a semi-dormant state, waiting another two years for your moment to shine, with only the heat of your 400 Watt reactor slowly winding down to keep you warm.

The decision is made to send your brother on a suicide mission. The only known non-planetary atmosphere in the solar system surrounds the moon Titan, and thus the adjustments are made to throw him into an orbit that will carry your speedy sibling past the moon and out of the plane of the Solar System. From here on out, he will race towards the outer reaches of all that we know at a much faster rate than you - over 17 kilometers per second - and away from any other targets of interest. He will keep transmitting, and one day, nearly a decade into the future, will take a photograph that will become iconic, that of the Pale Blue Dot, putting into the minds of many a sense of awe and yet fragility at the position of the Earth in relation to the void.

You repeat his path, passing by Saturn, taking photos much as you have done before, and while you have not changed in the four years since your launch, preparations are underway back at the place of your birth for your next mission.

You are aimed down a path that will carry you even further out, to Uranus and Neptune, and the antennae that have been the ears and voice of Earth are expanded from 26 to 34 meters to hear you as you pass farther and farther away. You will spend another four-plus years moving towards Uranus, and the antennae will grow to 70 meters as your voice grows faint; three more years, and you will pass by Neptune.

By now, the signal that was more than sufficient in your youth is approximately equal to that emitted by a digital watch, and with each moment the plutonium core of your reactor winds down further.

It is 1989, and you have done well, but you are not done yet. There will not be another planet, not even a single additional source of heat nor velocity from here on out.

Your energy budgets are recalculated, your mission extended.

By now, the thousands of people who were once committed to getting you off the ground have largely moved on; some have died, some have found new careers... and a select few still listen.

You faithfully make your way towards the outer edges of the system, growing colder, losing even the power necessary to keep yourself warm.

In 1998, the decision is made that you no longer have the energy to operate your sensors; the last of your eyes are closed, forever.

Your designers, perhaps optimistically, chose well when selecting your instrumentation - a number of packages remain relevant even beyond the orbits of the last of the gas giants.

By now, though, it has been two decades since your departure, and technology has not halted in its progression. Computers have advanced, entire architectures have come and gone, and the systems able to understand what you have to say gradually fall apart. There are few machines left in the world that can even understand your language, and they are kept together solely for your sake.

Perhaps it is pride, perhaps curiosity, that motivates men to maintain the vigil; whatever the case, you continue to do the only things you know.

Detect, transmit.

Another decade passes. You no longer have the budget to continue operating the gyroscopes that allow you to calibrate your magnetic sensors. Several years prior, you mis-interpreted a routine telemetry command as one to power up the heaters to one of your magnetometers, possibly due to bombardment by cosmic radiation; over a period of five days, this caused irreparable damage to this subsystem.

This is just one of a string of failures in individual components that comprise your being, inevitable yet saddening.

Your tiny heart has outperformed expectations, still operating at 58% of initial capacity, but there is no avoiding what is to come.

By the end of the year, you will no longer be able to do mass gyroscopic calibrations.

Within five years, you will no longer be able to operate your gyroscopes at all.

Within ten years, power will have to be shared between every piece of you just to do any readings whatsoever.

And within the next fifteen years, you will no longer be able to power a single thing. Your life will come to an end.

Still you plug away, driven by the single-minded determination of your design, and the momentum that carries you.

-

Perhaps, far into the future, you will serve one final purpose, communicating to someone traveling the great interstellar expanse a message from your home.

For within your decrepit bulk, battered by all the extremes of space, there resides a gold-plated copper disc, on which are recorded sights, sounds, and messages of the tiny blue dot upon which you were conceived, created, and from which you were launched.

-

This is a message of hope, and a record of things that were, originating in a time of strife and uncertainty, and its mere presence indicates a belief that there will be a tomorrow.

-

Even if that does not come to pass, you will continue on, perhaps one day the last record of a species that was, a species that dreamed and reached for the stars, a species that, once upon a time, sent out a few tenuous fingers into the great night sky and dared to dream that one day, they might follow.

Posted by vsrinivas at March 21, 2017 07:07 PM