December 31, 2022

2022

2022 Grab Bag:

- Finished my Masters degree (CSE @ UW)!; on top of that, took an Advanced Computer Architecture class & an Electric Grid regulation class from a WA UTC commissioner

-

Two ten-year anniversaries - ten years since my 4K bike ride from Baltimore to Portland (Chelsea from my year wrote the best retrospective); and ten years since I started working at Google

- Failed to hold a relationship together

-

Tens of thousands of miles of EV road-tripping!

Seattle, WA to Bodega Bay to North Lake Tahoe to Moab to Pullman, WA;

Seattle, WA to Dolores, CO and back;

Seattle, WA to Taos, NM and back;

-

A week sampling clover at Bodega Marine Lab, overlooking the Pacific Ocean

- Spent a month in a ~new place and state (Taos, NM)

- Donated a quarter of my income to climate and Effective Altruism organizations 😬 (details)

- Read 26 books; top three:

- Warmth, Daniel Sherrell - Talking about "The Problem" (Climate Change) in letters to a future child.

The author, Daniel Sherrell, is from New Jersey, not far from where and when I grew up; he works on climate advocacy in New York State. I found his perspective very relatable - he understands and draws on the technical, but writes the visceral. His evocation of love as fury is pretty powerful and stood out to me among climate writing.

- On Repentance and Repair, Danya Ruttenberg - Thinking about repentance, repair, and reconcilliation through a framework from Maimonides

The framework offered here is fairly different than the one I grew up with - it starts with objective statements of what happened; change to ensure the harm is not repeated; restitution and consequences; apology (delayed all the way to step 4!); and making different choices. As elaborated, it sounds like it would better address harm I have caused; it also seems like it'd be pretty demanding. I particularly appreciated an examination of something I do (apologize) but had never given great thought to.

- Ducks, Kate Beaton

- Warmth, Daniel Sherrell - Talking about "The Problem" (Climate Change) in letters to a future child.

-

First concert since the pandemic started (Gregory Alan Isakov at the Gorge)

-

Made jam and Ice Cream for the first time!

Made Fig and Pear, Peach, and Onion jams; Onion was the most successful -

Biked Mt. Constitution, part of the Sea to Sky Highway (BC Hwy 99), and Harvest Century

-

Grew tomatoes, a Sequoia, and potatoes (by mistake!)

- News story from the year that's stayed with me - Climate Change from A to Z, Elizabeth Kolbert, New Yorker Nov 2022

It's been an eventful, rich year. There's a lot I wish I'd done, a lot I wish I'd done better; but I tried new and hard things and learned from both the successes and failures.

See you in 2023!

March 21, 2022

How much does it cost to drive an electric car?

In July 2021, I bought an electric car ("EV"), a Chevy Bolt. I bought it in the wake[1] of the Pacific Northwest heat wave - intellectually I know that we must stop using fossil fuels as fast and as completely as possible; but after the heat wave I had to switch myself. I could not continue to drive a gas car, not on road trips to outdoor places I love, knowing I was making the next heat wave that much more likely or that much more damaging.

Electric cars are, first, cars; mostly, they drive and operate like gas ("ICE") cars. However there is a learning curve, especially if you’re road-tripping in one - learning when to charge and how much to charge at each stop; and how to manage energy and drive efficiently when needed or when to sprint. They promise a lot lower lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions [2][3], lower operating costs, lower maintenance costs, and never having to go to a gas station again; on the other hand they bring long charging times and have limited charging stations.

Climate is why I'm driving an electric car above all things; however I’d like to share a bit about how much it costs to drive electric by looking a whole month, February 2022 - let's see if the promise of lower operating costs bears out here.

I don’t have a daily commute - I work from home and have access to "L1" charging (a regular 120 volt outlet, $0.13 per kWh) at my apartment. However I drove a lot in February -- my girlfriend and I took two road trips, Seattle, WA to Champoeg State Park in Oregon for a camping/snowshoeing/birthday trip; and Seattle, WA to Gibsons, BC to visit family. All told, we drove 1,156 miles, totalling $53.80, averaging 4.6 cents per mile ($34.40 in DC Fast Charging costs and $19.40 in additional electric bills from apartment charging).

A gas car that averages 36 miles per gallon would’ve taken 32 gallons of gas to drive the same distance. At February’s average per-gallon price of $4.05 in Seattle, it would have cost $130, or roughly 11 cents per mile; at today’s gas price, it would have cost just over $150, or 13 cents per mile.

| Date | Odo | Charge % (kWh) | Where | How? | Cost |

| 2/4 | 11791 | 67% -> 69% (1.3 kWh) | Seattle, WA | L1 (120v outlet) | $0.16 |

| 2/4 | 11899 | 42% -> 60% (11.7 kWh) | Seattle, WA | L1 (120v outlet) | $1.52 |

| 2/5 | 11915 | 52% -> 93% (26.6 kWh) | Seattle, WA | L1 (120v) | $3.48 |

| 2/11 | 12113 | 15% -> 23% (5.2 kWh) | Wilsonville, OR | DC Fast Charger, Wilsonville Public Library | $6.21 |

| 2/11 | 12125 | 20% -> 42% (14.3 kWh) | Champoeg, OR | Champoeg State Park RV site, L1 (120v) | $0 |

| 2/12 | 12137 | 39% -> 74% (22.75 kWh) | Wilsonville, OR | DC Fast Charger, Wilsonville Public Library | $5 |

| 2/12 | 12251 | 24% -> 62% (24.7 kWh) | Portland, OR | East Portland | $5 |

| 2/12 | 12348 | 15% -> 62% (30.5 kWh) | Centralia, WA | Centralia Civil Aviation | $10.94 |

| 2/13 | 12441 | 15% -> 40% (16.2 kWh) | Seattle, WA | L1 (120v outlet) | $2.10 |

| 2/13 | 12497 | 19% -> 33% (9.1 kWh) | Tacoma, WA | L2, Tacoma Zoo | $0 |

| 2/13 | 12545 | 13% -> 49% (23.4 kWh) | Seattle, WA | L1 (120v outlet) | $3.04 |

| 2/14 | 12554 | 44% -> 92% (31 kWh) | Seattle, WA | L1 (120v outlet) | $4.03 |

| 2/18 | 20457 km (we _were_ in Canada!) | 23% -> 88% (42.2 kWh) | Gibsons, BC | L1 (120v outlet) | - |

| 2/21 | 12801 | 44% -> 70% (16.9 kWh) | Bellingham, WA | DC Fast Charger, Bellingham Whole Foods | $7.25 |

| 2/22 | 12883 | 27% -> 87% (39 kWh) | Seattle, WA | L1 (120v outlet) | $5.07 |

| Total | $53.80 |

Looking at a full month of electric car charging has been instructive - home (even 120v) charging is very cheap per-mile; DC Fast Charging costs are variable. Even the most expensive fast charging sessions (half the battery!) was under $11 though. Electric cars currently have higher initial prices than gas ones and there is not a robust used market available; but once those initial costs are overcome, driving costs are lower.

I will write about road-tripping in the summer and winter with a Bolt soon; until then, hope this snapshot of charging costs is helpful!

[1]: I mean wake in the full sense of the word.

[2]: https://environment.yale.edu/news/article/yse-study-finds-electric-vehicles-provide-lower-carbon-emissions-through-additional

[3]: https://blog.ucsusa.org/dave-reichmuth/are-electric-vehicles-really-better-for-the-climate-yes-heres-why/

July 08, 2021

STS135 - Ten Years After

Ten years ago today was the final launch of the Space Shuttle, STS-135. The Space Shuttle Atlantis flew a crew of four on a final support mission to the International Space Station and closed out the then 30-year-old Space Shuttle Program.

I grew up with imagery and stories of the Space Shuttle; I had the extraordinary chance to be at Cape Canaveral for the final launch; on this day, it is good to remember that moment as it was.

Under a sputtered white Canaveral sky. Weather is good; go STS135!

— Venkatesh Srinivas (@signal_vs_noise) July 8, 2011

I wrote to a friend shortly after -

This past weekend I drove down to Florida for the STS135 launch; watched from the Kennedy Space Center causeway, ~4mi out. The launch ... I'm not sure what to say about it, I'm still processing. I can say what it was like physically; at ignition, there was an great grey cloud of exhaust from the launchpad; a few seconds later, two incredible plumes of orange-white fire, the SRB exhaust plumes. The exhaust was superbright, throwing light into the grey day like little else I've ever seen. In just a few seconds the stack hit a cloud and lit it orange-white and it was gone.

A little after, there was a pressure wave across the water; it was both sound and physical force. Not overwhelming; but powerful, deep. Like hundreds of heavy trains all rolling at once near you. And then it too was gone.

[...]

I left with two things; the SRB fire and memory of lying on the grass by the water, commanding away clouds in the grey sky.

May 08, 2021

gVNIC

A couple of months ago, Google Cloud launched gvnic, a new paravirtual network interface for virtual machines in Google Compute Engine. gvnic offers higher performance than and new features over the prior paravirtual network interface in GCE, virtio-net.

Welcome to Ubuntu 20.04.2 LTS (GNU/Linux 5.4.0-1036-gcp x86_64) * Documentation: https://help.ubuntu.com * Management: https://landscape.canonical.com * Support: https://ubuntu.com/advantage System information as of Sat Feb 20 03:49:30 UTC 2021 System load: 0.08 Processes: 103 Usage of /: 14.9% of 9.52GB Users logged in: 0 Memory usage: 5% IPv4 address for ens4: 10.240.0.29 Swap usage: 0% 1 update can be installed immediately. 0 of these updates are security updates. To see these additional updates run: apt list --upgradable The list of available updates is more than a week old. To check for new updates run: sudo apt update Last login: Sat Feb 20 03:42:19 2021 from 173.194.90.36 extrudedaluminiu@instance-2:~$ lspci -nn 00:00.0 Host bridge [0600]: Intel Corporation 440FX - 82441FX PMC [Natoma] [8086:1237] (rev 02) 00:01.0 ISA bridge [0601]: Intel Corporation 82371AB/EB/MB PIIX4 ISA [8086:7110] (rev 03) 00:01.3 Bridge [0680]: Intel Corporation 82371AB/EB/MB PIIX4 ACPI [8086:7113] (rev 03) 00:03.0 Non-VGA unclassified device [0000]: Red Hat, Inc. Virtio SCSI [1af4:1004] 00:04.0 Ethernet controller [0200]: Google, Inc. Compute Engine Virtual Ethernet [gVNIC] [1ae0:0042] 00:05.0 Unclassified device [00ff]: Red Hat, Inc. Virtio RNG [1af4:1005] |

I worked on gvnic for nearly three years (though it was some time ago); It is exciting to see a new paravirtual device of this scope reach General Availability!

A new paravirtual device represents a VM guest/hypervisor ABI and requires careful attention to detail - we needed to ensure that the ABI is a good match to VM guest requirements, to a hypervisor and underlying network infrastructure properties, and is designed with forward-evolution and versioning in mind. There are tradeoffs at multiple levels - for example, VM guests and hypervisors may have different preferences for where in memory transmit or receive frames live and how they're scattered/gathered; whether receive frame headers are more efficient in-line or out-of-line; and hundreds of other decisions that impact system performance and maintainability.

Congratulations to everyone involved in the design and launch of the system; and to everyone who uses it, I hope it works well for you!

July 02, 2019

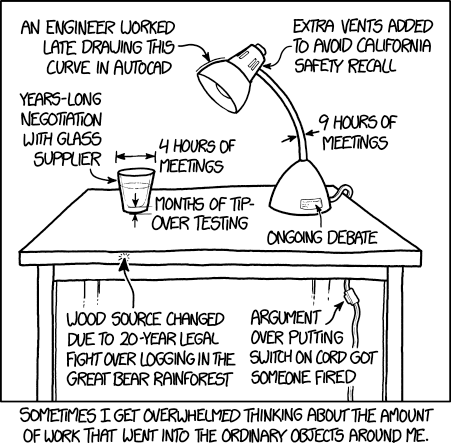

Organizations I've supported in 2018 and 2019 H1

Early in 2017, I committed to support a number of nonprofits and civil society organizations, particularly focused on climate change. I wrote about the organizations I planned to support and why - Organizations I'm supporting (2017) and I wrote a follow-up of what I ended up doing - Organizations I've supported in 2017.

In 2018, I wrote an updated plan - Organizations I'm supporting in 2018. I added a number of non-proliferation and think-tank organizations in preference to direct assistance and I slightly biased in favor of local and regional organizations relative to national ones.

I'm writing to share what I've been doing / what's worked for me and highlight organizations or types of organizations worth thinking about out.

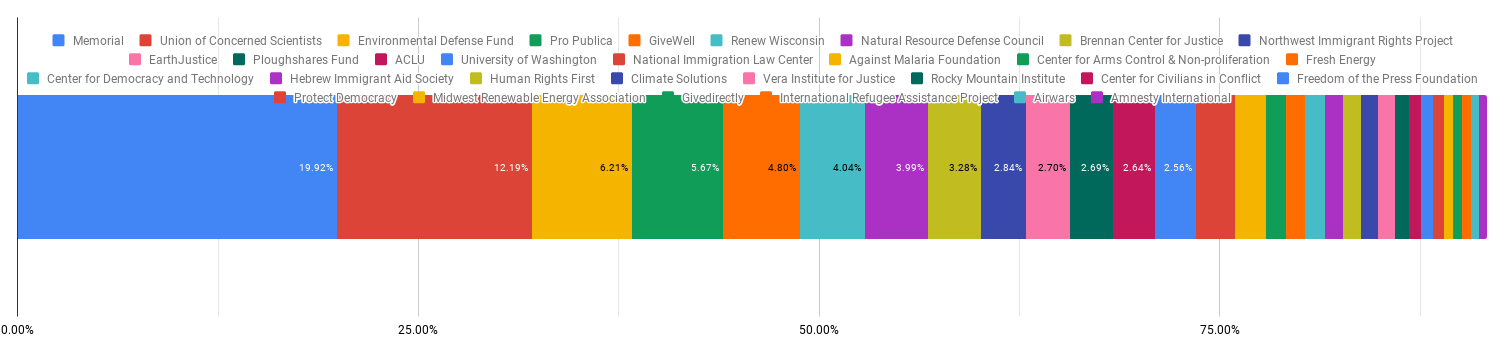

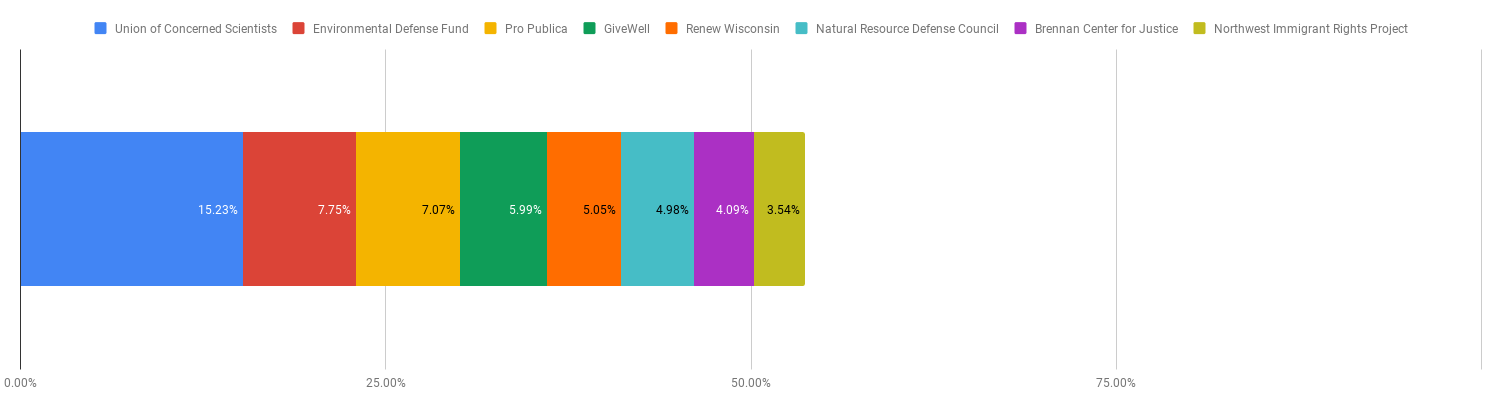

In 2018, I donated 321 individual times to 68 distinct organizations. Donations were skewed - the top 7 organizations received > 50% of all donations, the top 12 received 75%.

2018 Overall

2018 75%

2018 50%

Top organizations -

- Union of Concerned Scientists

- Environmental Defense Fund

- Pro Publica - Nonprofit investigative newsroom

- RENEW Wisconsin

- Natural Resources Defense Council

- Brennan Center for Justice

- Northwest Immigrant Rights Project ( > 50%)

- GiveWell

- EarthJustice

- Ploughshares Fund - Grant-making nonprofit focused on nuclear nonproliferation

- ACLU

- National Immigration Law Center ( > 75% )

I’d like to highlight RENEW Wisconsin and Fresh Energy - both state-level organizations advocate for cleaner energy generation and access in Wisconsin and Minnesota respectively; I think they are high-leverage organizations given the carbon intensity of the MISO region and the possibility of state-level climate action. Both were new to the list in 2018.

In 2018 I also opened a Donor Advised Fund (DAF), presumptuously named Memorial. A Donor-Advised Fund is a designated account at a “nonprofit”, often associated with a financial services firm (I use Fidelity’s, for example); contributions to the fund are considered 501(c)3 donations and may be invested and later donated to a separate non-profit. DAF’s do have associated fees; these fees may mean they are not a good choice in all circumstances. I’ve chosen to invest in a balanced mix of US stock / US bond index funds and do not use Environmental/Sustainable/Governance (ESG) funds, though they are available.

I use a DAF for two reasons - 1) Better recordkeeping and 2) To defer year-end donations into the following calendar year, to take advantage of annual corporate donation matching.

Total direct donations in 2018 were 92% of 2017’s total; including pre-funding the Donor-Advised Fund raises that to 107%. As a percentage of my total income, this was between 11% and 14%, again depending on whether the pre-funding was included.

In 2018, I found out about the Effective Altruism (EA) community; EA aims to apply analysis to philanthropy - where can a dollar do the most good (by a common metric, years of life, quality-weighted, per intervention), with an emphasis on measuring outcomes and the good a marginal dollar can do. EA-favored nonprofits have focused on public health (ex: malaria control) and existential risks in the recent past.

I am convinced the EA approach is valuable, but the metric undervalues indirect work civil society may do, such as advocacy or informing policy.

In October 2018, I took the EA-associated Giving What We Can Pledge:

“I recognize that I can use part of my income to do a significant amount of good. Since I can live well enough on a smaller income, I pledge that for the rest of my life or until the day I retire, I shall give at least ten percent of what I earn to whichever organisations can most effectively use it to improve the lives of others, now and in the years to come. I make this pledge freely, openly, and sincerely.”

I missed this target in 2018, though I gave 3.8% overall to GiveWell, GiveDirectly, Against Malaria Foundation, Future of Life Foundation, and No Lean Season.

In 2018, I contributed to a number of state and federal election campaigns; contributions can be viewed through the FEC site but are not included above.

In 2018, I also purchased 20 metric tons of CO2e offsets, via methane flaring, from a private provider.

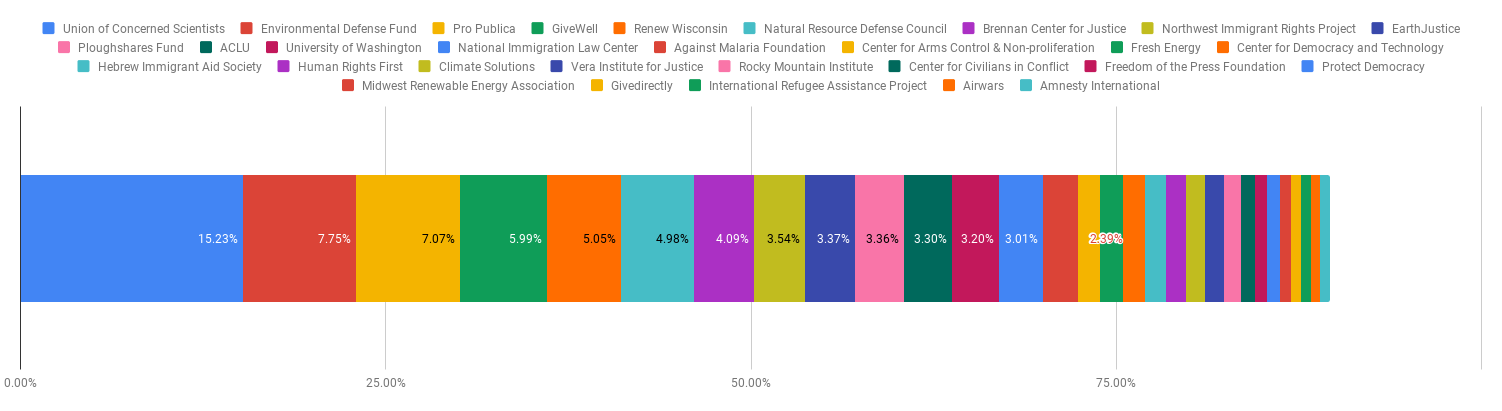

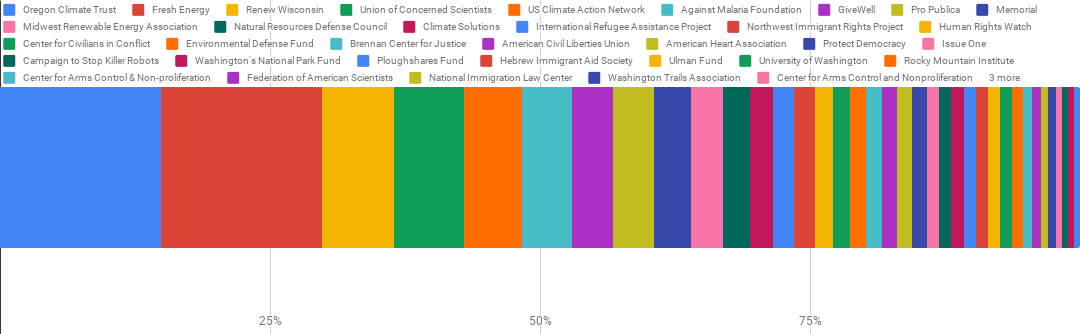

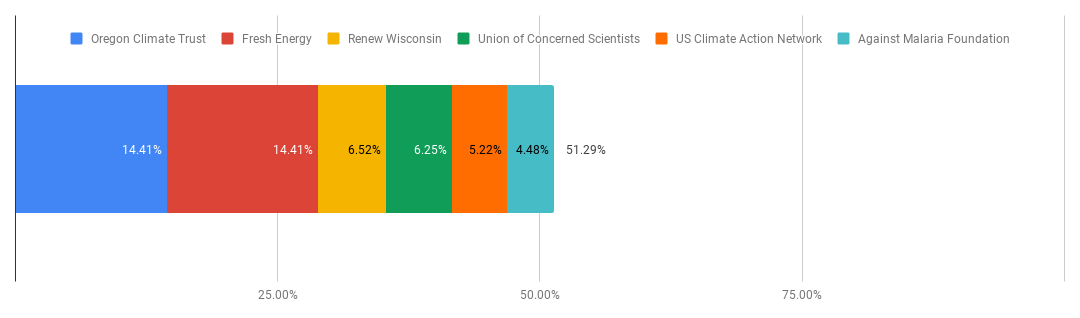

In the first half of 2019, I’ve donated 135 individual times to 48 distinct organizations. Once again, donations were skewed - the top 5 organizations received > 50% of all donations, the top 15 received > 75%.

2019 Overall

2019 50%

Top organizations -

- Oregon Climate Trust - Oregon organization administering Oregon Carbon Dioxide Standard, undertaking offset programs

- Fresh Energy - Minnesota energy transition / clean energy organization with a long track record (~1992). Was involved in the closure of the Sherco I and II (coal) generating stations in Becker, MN

- RENEW Wisconsin - Wisconsin advocacy organization, focuses on interfacing with PUC and supporting "Focus on Energy" program

- Union of Concerned Scientists

- US Climate Action Network

- Against Malaria Foundation (> 50%)

- GiveWell

- Pro Publica

- Midwest Renewable Energy Association

- Natural Resources Defense Council

- Climate Solutions - Oregon and Washington

- International Refugee Assistance Project

- Northwest Immigrant Rights Project

- Human Rights Watch

- Center for Civilians in Conflict (> 75%)

In 2019, I've focused on state- and regional- clean energy and climate organizations (Oregon Climate Trust, Fresh Energy, Renew Wisconsin, Wind on the Wires, Midwest Renewable Energy Association, Climate Solutions...). There have been too many failures of large climate projects, from regional transmission projects, to carbon taxes (Washington has failed to pass three times), to Oregon's HB2020, to V.C. Summer's abandonment. At the same time, there have been and state- and regional-level successes; focusing on the organizations that have made them possible buys space and time and window for larger-scale projects, I think.

Total direct donations in 2019 so far have been 90% of 2018’s yearly total and 84% of 2017’s total. As a percentage of my income so far, this has been between 16% and 19%, depending on whether Donor-Advised Fund contributions or outflows are credited.

I've met roughly 10% of my Effective Altruism Giving Pledge target this year. I plan to at least meet 2018's mark, though am hoping to meet the whole target.

I haven't purchased any carbon offsets this year; I am not sure as to whether or how effective they are; I'd appreciate any thoughts about them.

I've enjoyed this three-year-long giving project; I'd appreciate any thoughts about what I could be doing better/differently and anything else I should check out. I'd appreciate any thoughts about how I might contact and chat with the non-profits I support and what sort of metrics would be appropriate for climate or civil organizations. Or any thoughts about how to present this data better!

March 21, 2018

Organizations I'm supporting in 2018

Early in 2017, I committed to support a number of nonprofits and civil society organizations; I wrote about the organizations I planned to support and why: Organizations I'm supporting this year - broadly I planned to focus on civic and environmental groups. Last December, I looked back at the year and where I followed or deviated from plan: Organizations I've supported in 2017.

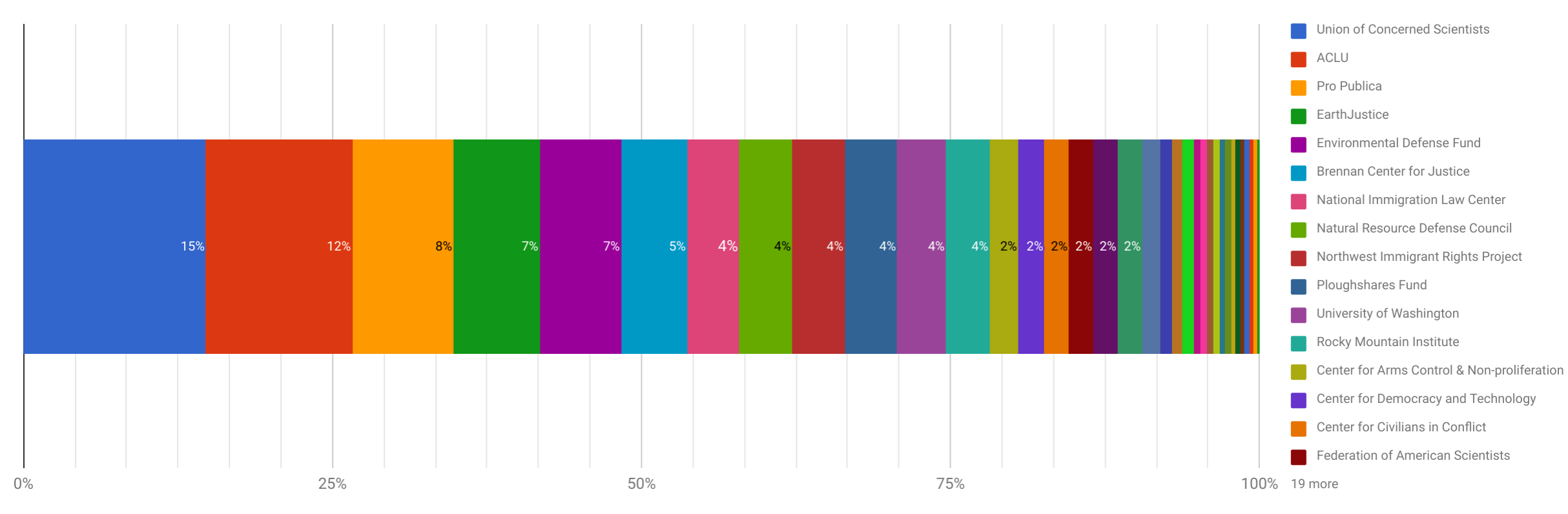

This year, I continue to support a broad set of nonprofits/organizations, primarily in civic and environmental sectors. New this year, I have added nuclear nonproliferation and science & society organizations (ex: Federation of American Scientists, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists) and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. Through the year, I plan to support the organizations below proportionally and to highlight specific work each/any does (such as policy papers/testimony/etc) that I think is important.

| Union of Concerned Scientists | 15% | |

| American Civil Liberties Union | 12% | |

| Pro Publica | 8% | Nonprofit newsroom; also serves as a resource for traditional news organizations |

| EarthJustice | 7% | |

| Environmental Defense Fund | 7% | |

| Brennan Center for Justice | 5% | |

| National Immigration Law Center | 4% | |

| Natural Resource Defense Council | 4% | |

| Northwest Immigrant Rights Project | 4% | |

| Ploughshares Fund | 4% | Grant-making nonprofit, focused on nuclear nonproliferation |

| University of Washington Climate Impacts Group, various | 4% | |

| Rocky Mountain Institute | 4% | Studies & writes on climate change, energy, and decarbonization |

| Center for Arms Control & Non-proliferation | 2% | |

| Center for Democracy and Technology | 2% | |

| Center for Civilians in Conflict | 2% | |

| Federation of American Scientists | 2% | Runs extraordinary Government Secrecy Project; provided recent comments on autonomous weapon systems |

| International Refugee Assistance Project | 2% | |

| United to Protect Democracy | 2% |

This does not include donations to candidates for office / PACs, raw data for those contributions are available on the FEC website. This does not include my carbon offset purchases at scale either.

I think public lists & commitments valuable to cast lights on work at civic nonprofits and to mobilize further support. If you know of any interesting civic, nonproliferation, or climate change nonprofits doing good work, I'd be interested to hear!

December 28, 2017

Organizations I've supported in 2017

"I have a little hope that America’s amazingly robust and wealthy civil society, which is unlike any other civil society in the world, ever, will change the situation, or will make it progress differently." - Masha Gessen, Apr 2017

Early in 2017, I committed to supporting a number of nonprofits; I wrote about the organizations I planned to support and why. I focused on civil society and on climate change organizations, with a bias towards legal groups. (I was inspired by DJ Capelis's post earlier).

2017 brought disruptions, natural triggers were amplified into logistic and human disasters. 2017 brought old fears into new focus - nuclear proliferation, civil-military relationship strains, use and control of force questions. Progress addressing climate change (emissions and decarbonization) has been disappointing. I found it difficult to sustain attention and focus on particular problems.

I did not foresee how 2017 would and did proceed.

The year also brought the incredible strength and depth of our civil society and their role in the public sphere into focus - legal organizations via lawsuits as expected, but policy and journalism organizations to educate and focus attention too. I did not know about whole classes of organizations in the policy and public education spaces just ten months ago, now I am deeply grateful for their works.

Breaking down my donations ---

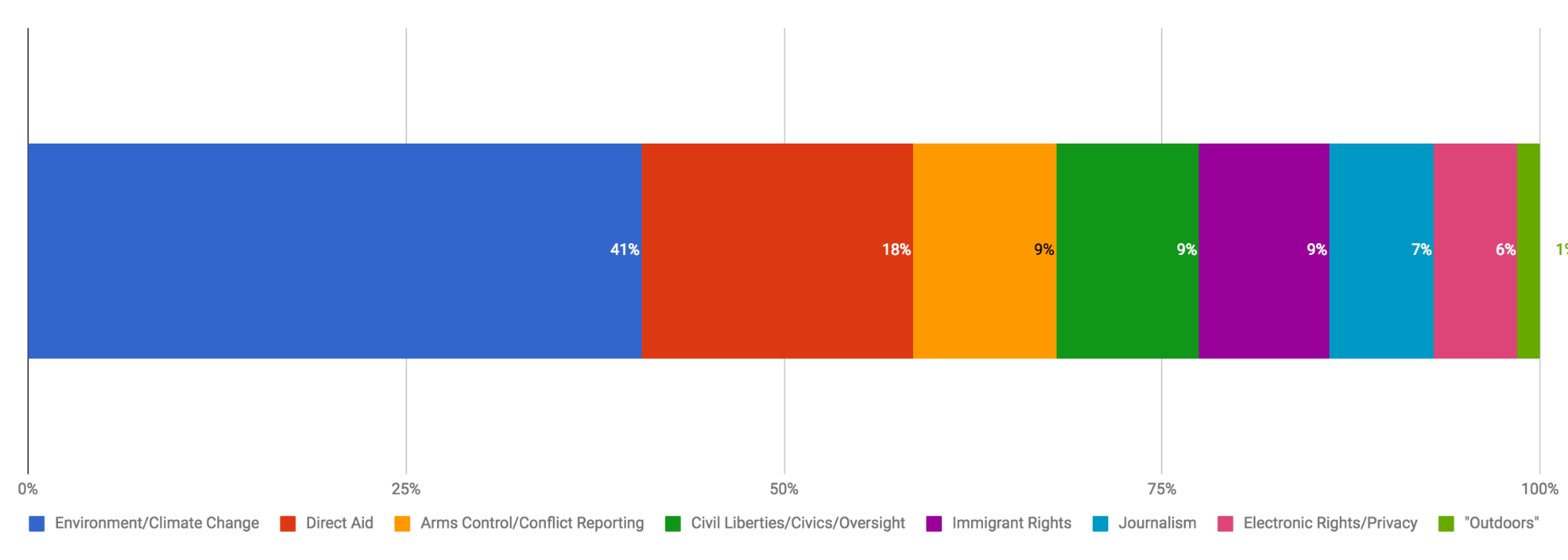

By "area":

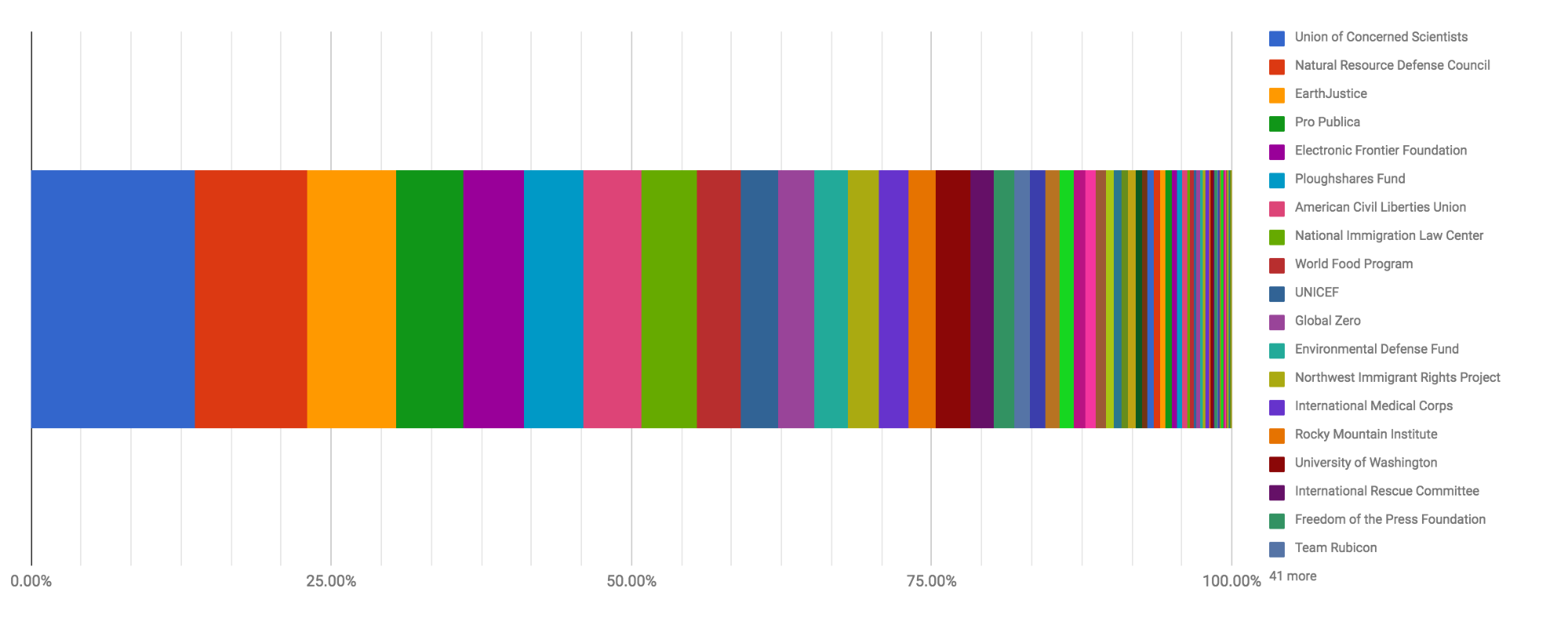

By organization:

Top organizations:

Top organizations:

| Union of Concerned Scientists | 13.6% |

| Natural Resource Defense Council | 9.3% |

| EarthJustice | 7.3% |

| Pro Publica | 5.6% |

| Electronic Frontier Foundation | 5.0% |

| Ploughshares Fund | 4.9% |

| American Civil Liberties Union | 4.9% |

| National Immigration Law Center | 4.5% |

| World Food Program | 3.6% |

| UNICEF | 3.0% |

| Global Zero | 3.0% |

| University of Washington Climate Impacts Group | 2.9% |

| Environmental Defense Fund | 2.75% |

| Northwest Immigrant Rights Project | 2.6% |

| International Medical Corps | 2.5% |

| Rocky Mountain Institute | 2.2% |

| International Rescue Committee | 1.9% |

| Freedom of the Press Foundation (Signal) | 1.6% |

| Team Rubicon | 1.3% |

| International Refugee Assistance Program | 1.25% |

| Brennan Center for Justice | 1.2% |

| Medicines Sans Frontieres | 0.9% |

| Mercy Corps | 0.9% |

| World Resources Institute | 0.9% |

| Let America Vote | 0.6% |

| Airwars | 0.6% |

| Washington National Parks Fund | 0.6% |

For the most part, I donated to the organizations I committed to. Standout differences --

- I did not expect to have to think about weapons control and nonproliferation; and I did not know about the work of Ploughshares or Global Zero at the start of the year

- I did not know about smaller "think-tank" environmental organizations, such as Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), Resources for the Future, Ceres, etc. at the start of the year

I did not include donations to political candidates or organizations above.

I also began purchasing carbon offsets this year in bulk, as a direct means to mitigate unavoidable personal emissions and in excess of what zeroth-order calculators claim. I purchased 110 metric tons of offsets from the Bonneville Environmental Foundation, from cooleffects, from the Colorado Carbon Fund, and from a private provider. (Not included above). I am not sure about the effectiveness of carbon offsets to in bulk to mitigate climate change and would appreciate any data or arguments either way. Without additional arguments, I plan to purchase offsets for ~1000 metric tons through the end of 2018.

March 21, 2017

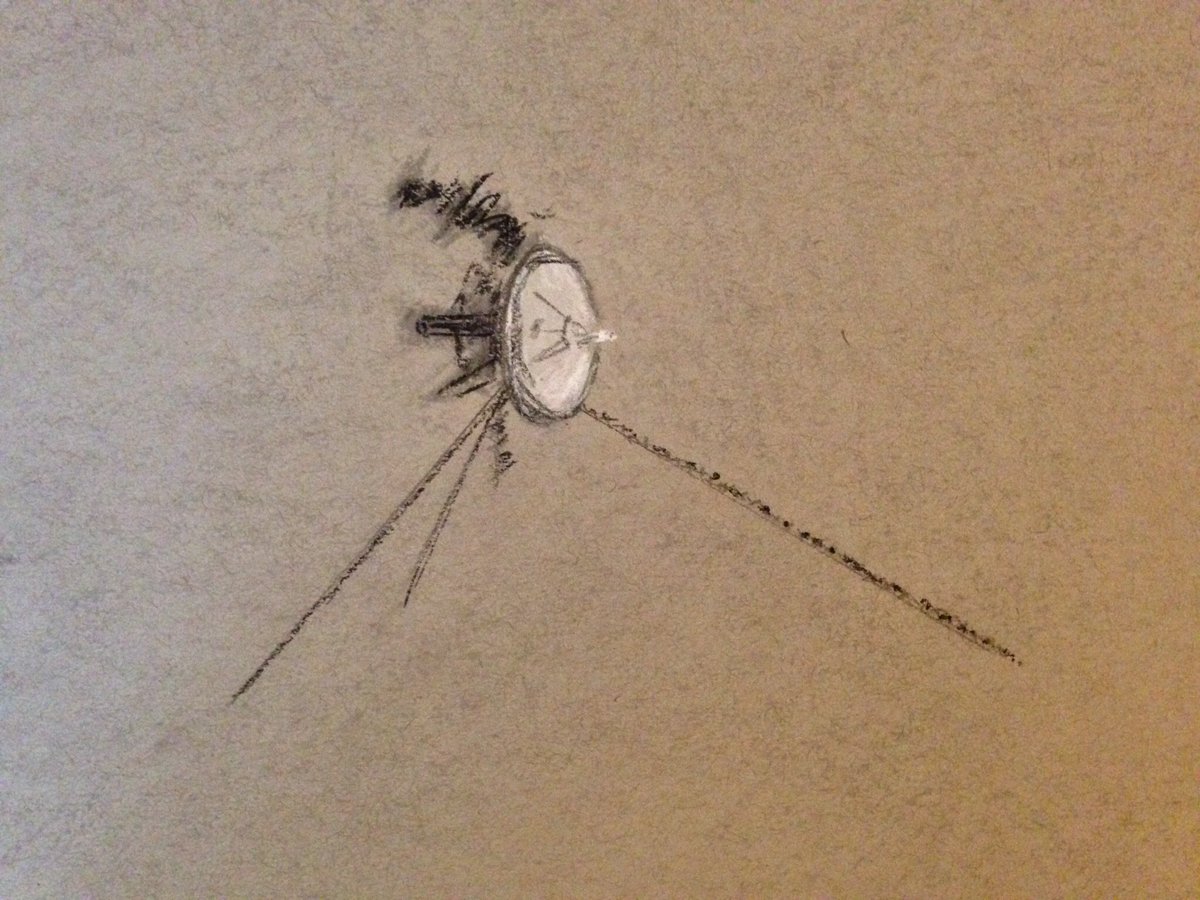

Detect. Transmit.

2017 is the 40th anniversary of the launch of the twin Voyager spacecraft. I found this essay about Voyager on the Internet years ago - I don't remember where and I can't find any breadcrumbs. I'm sharing it, lightly edited, as one of the finest space program essays I've ever found.To imagine what being the Voyager probe would be like, consider the following:

Your life begins, conceived during the mid-60s golden years of the space program.

The core concepts of your design are settled during the first years of that decade, and refined for fifteen years as different attempts are made to extend the reach of man's knowledge first to the skies, then to our nearest neighbors.

Your idea forms in an era of slide-rules and pencils, as astronomical calculations reveal a particularly fortuitous alignment of the outer planets in the coming decade, one that will slingshot you to the outer reaches of the solar system, hopping from planet to planet.

Slowly, your design is solidified, using the best space-worthy technology man has to offer, instrumentation, structure, power, from the peak of each discipline of a nation. The brightest engineers and scientists painstakingly weigh each possible ounce of material with which to construct you, judging the possible benefits that can be attained versus the energy you'll need to accomplish your journey.

After all, the road that you will travel has never before been attempted by this race of surface-dwelling primates, they have the barest idea of what to study.

As the day of your birth approaches, plans are completed, mass and energy budgets are finalized, and your fetus takes form in a sterile clean room. Engineers calibrate your eyes and ears, build each part of your systems from scratch, and then test and re-test until they're as certain as they can be that all of your senses are ready for the trials you will face.

You're folded into the space probe equivalent of the fetal position, your sensors and reactor folded to fit inside the payload compartment of a nearly one and a half million pound rocket fueled by some of the most dangerous compounds known to man. At nearly one thousand times your total mass, this mountain of explosives will catapult you away from the last truly warm place you will ever know, away from the light and heat and activity of your womb, and into the cold blackness that will define you as a success, or perhaps as a failure.

For all the care that has been taken in your construction, if this unstable pillar that provides your birthing contractions were to explode, you would end as just another footnote in a failed attempt to reach into the skies.

-

Fortunately, you are borne into the heavens cleanly; your delivery proceeds exactly as planned, and you begin your travel on the path that was chosen well before your birth.

-

However, your tiny brain, barely a half a megabyte in capacity in today's terms, spread across six different subsystems, gets confused: you are dizzy, disoriented, and lost. Your eyes and ears and heart have all stretched out as they should, and everything is as it was designed to be, and yet you believe yourself lost much further out into the void than you truly are, and you scream the wail of a lost child, long and piercing, unresponsive to any attempt to convince you that you're alright.

A routine in your solid core memory kicks in, and you obey it, and you do the only thing you know. Every part of you shuts down, with the exception of your eye and your tiny legs, the gas thrusters that will help you orient yourself towards the warm light of the sun.

You look around you, and locate this beacon, and as you twist and turn your senses gradually return and you realize that all is well. Finally, you call back home and tell them that all is well, after all. The frantic worrying over your extended silence is over, although you have no way of telling them, or even knowing, what actually went wrong.

You are on your way, and for now they will have to have faith in you.

You are not expected to live much past three years, but your birth is a moment of exultation and relief. You make your way toward your destiny, listening for your creators as you were designed to do, when something happens - or more accurately, nothing.

They are so engrossed in preparing to deliver your twin brother that they neglect you at just the wrong time, and you, hearing nothing, assume that you've gone deaf.

You strain with one ear, then the other, and finally the words you've been awaiting arrive, but the struggle has damaged something vital. One of your ears is now completely deaf, and the other has been damaged irreparably, a million miles from home.

New instructions are sent to you, and you adjust as time goes on, but your hearing will never be quite the same.

And so you wait, almost two long years traveling through the blackness, measuring, sensing, recording all you can detect and sending it back home as a constant yet paltry stream of information, and try not to get too jealous as your twin reaches the first of the outer planets, Jupiter, four months ahead of you.

Yet it will pave the way for your own triumph, for this is the closest anything made by man will have ever, until this time, approached the giant, and its work will help refine what you are to do.

You open your eyes, pitiful in their abilities - a pair of sensors 800 pixels on each side - and every 48 seconds for the next few months, you will repeatedly record what you can see, tell Earth, then repeat, changing filters as you are told to extract as much out of this time as you can.

You help scientists make their careers: between you and your brother, astronomers over 700 million miles away find evidence for volcanism on Io, rings around the planet itself, and are able to study the furious hurricane known as the Great Red Spot in heretofore unthinkable detail.

In approaching the planet, you maneuver so as to steal a tiny bit of its energy to turn into a huge change in course and gain in speed for yourself, sending you barreling off towards the sixth planet, Saturn; and again, you enter a semi-dormant state, waiting another two years for your moment to shine, with only the heat of your 400 Watt reactor slowly winding down to keep you warm.

The decision is made to send your brother on a suicide mission. The only known non-planetary atmosphere in the solar system surrounds the moon Titan, and thus the adjustments are made to throw him into an orbit that will carry your speedy sibling past the moon and out of the plane of the Solar System. From here on out, he will race towards the outer reaches of all that we know at a much faster rate than you - over 17 kilometers per second - and away from any other targets of interest. He will keep transmitting, and one day, nearly a decade into the future, will take a photograph that will become iconic, that of the Pale Blue Dot, putting into the minds of many a sense of awe and yet fragility at the position of the Earth in relation to the void.

You repeat his path, passing by Saturn, taking photos much as you have done before, and while you have not changed in the four years since your launch, preparations are underway back at the place of your birth for your next mission.

You are aimed down a path that will carry you even further out, to Uranus and Neptune, and the antennae that have been the ears and voice of Earth are expanded from 26 to 34 meters to hear you as you pass farther and farther away. You will spend another four-plus years moving towards Uranus, and the antennae will grow to 70 meters as your voice grows faint; three more years, and you will pass by Neptune.

By now, the signal that was more than sufficient in your youth is approximately equal to that emitted by a digital watch, and with each moment the plutonium core of your reactor winds down further.

It is 1989, and you have done well, but you are not done yet. There will not be another planet, not even a single additional source of heat nor velocity from here on out.

Your energy budgets are recalculated, your mission extended.

By now, the thousands of people who were once committed to getting you off the ground have largely moved on; some have died, some have found new careers... and a select few still listen.

You faithfully make your way towards the outer edges of the system, growing colder, losing even the power necessary to keep yourself warm.

In 1998, the decision is made that you no longer have the energy to operate your sensors; the last of your eyes are closed, forever.

Your designers, perhaps optimistically, chose well when selecting your instrumentation - a number of packages remain relevant even beyond the orbits of the last of the gas giants.

By now, though, it has been two decades since your departure, and technology has not halted in its progression. Computers have advanced, entire architectures have come and gone, and the systems able to understand what you have to say gradually fall apart. There are few machines left in the world that can even understand your language, and they are kept together solely for your sake.

Perhaps it is pride, perhaps curiosity, that motivates men to maintain the vigil; whatever the case, you continue to do the only things you know.

Detect, transmit.

Another decade passes. You no longer have the budget to continue operating the gyroscopes that allow you to calibrate your magnetic sensors. Several years prior, you mis-interpreted a routine telemetry command as one to power up the heaters to one of your magnetometers, possibly due to bombardment by cosmic radiation; over a period of five days, this caused irreparable damage to this subsystem.

This is just one of a string of failures in individual components that comprise your being, inevitable yet saddening.

Your tiny heart has outperformed expectations, still operating at 58% of initial capacity, but there is no avoiding what is to come.

By the end of the year, you will no longer be able to do mass gyroscopic calibrations.

Within five years, you will no longer be able to operate your gyroscopes at all.

Within ten years, power will have to be shared between every piece of you just to do any readings whatsoever.

And within the next fifteen years, you will no longer be able to power a single thing. Your life will come to an end.

Still you plug away, driven by the single-minded determination of your design, and the momentum that carries you.

-

Perhaps, far into the future, you will serve one final purpose, communicating to someone traveling the great interstellar expanse a message from your home.

For within your decrepit bulk, battered by all the extremes of space, there resides a gold-plated copper disc, on which are recorded sights, sounds, and messages of the tiny blue dot upon which you were conceived, created, and from which you were launched.

-

This is a message of hope, and a record of things that were, originating in a time of strife and uncertainty, and its mere presence indicates a belief that there will be a tomorrow.

-

Even if that does not come to pass, you will continue on, perhaps one day the last record of a species that was, a species that dreamed and reached for the stars, a species that, once upon a time, sent out a few tenuous fingers into the great night sky and dared to dream that one day, they might follow.

February 12, 2017

Organizations I'm supporting this year

(updated 3/05)

I was inspired by DJ Capelis's post to discuss the nonprofits and funds I'm supporting this year and the reasons behind my choices.

A few themes -

-

Nonprofits are an important part of society in that they bring together people who have been thinking about and working on specific problems for a long time.

However - Nonprofits are not the answer to every problem and are not going to be able to right or even mitigate every harm. This is not the computer networking - there is no "routing around" damage here and now.

-

A focus on legal organizations - Legal organizations (like the ACLU and EarthJustice) work through litigation, lobbying, and comment on rulemaking.

Legal victories do not stand alone; at best they can buy space and time for public action and consensus to cement rulings or rules into the society.

-

Allocation - Approximately half my donations are to civil organizations and half are to Environmental/Climate Change organizations

- The American Civil Liberties Union - The ACLU is a traditional bulwark in defense of civil liberties. The organization is large and capable and there are legal fights only they can sustain.

Of note - the ACLU is actually two organizations, a 501c4 (The American Civil Liberties Union) and a 501c3 (The American Civil Liberties Union Foundation). The 501c4 can spend on lobbying where the Foundation cannot, so I give to them.

- Pro Publica is a news organization focused on investigative journalism and long-form stories. The series "Killing the Colorado" (river) was deeply interesting and supporting investigative journalism is important to me.

- Brennan Center for Justice - a law-advocacy organization at NYU; has an ongoing project dedicated to Voting Rights and ballot access

- Let America Vote - a new 501c4 organization focused on access to the ballot. I donated mainly because of the nature of the problem and the track record of its founders (Jason Kander).

- National Immigration Law Center

- Northwest Immigrant Rights Project

I consider climate change to be a unique, grave threat. Environmental systems have complex dynamics and momentum - delayed intervention has been and will be much more expensive than earlier intervention and may be limited to mitigation.

- The Union of Concerned Scientists

- EarthJustice is an environmental law organization; they have been the legal force in support of the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal project.

- Environmental Defense Fund is another environmental law organization

- Natural Resources Defense Council

- University of Washington Climate Impacts Group - the CIG is a group at UW studying and modeling concrete impacts of climate change.

- Columbia University Center for Climate and Life - is a group which provides direct funding and grants to climate change and mitigation research.

June 06, 2014

Trust Fall

Ally from my team shared this memory of our day on the 4K two years ago....

"When we got into the Grace United Methodist Church, the pastor took us outside to show us the backyard.

We proceeded to play outside all afternoon with me, Sohum and Dale climbing trees and then Yoshi leading

us in core exercises. There are so many moments that I look around and realize how quickly I have

grown to love this team. We were playing outside after doing core when we all ended up underneath

the pavilion chatting. We were kind of jumping around the area and I ended up standing on one of the picnic

tables. I jokingly turned around and said, “trust fall” like I was going to fall backwards. Everyone who was there

automatically put their arms out in front of them and all it took was for me to turn around and say “really? okay”

to go through with it and have no anxiety at all about it. Its a strange feeling but when it’s right, you just know."

I will add "And Kevin Cochran hiding my duffle bag in a tree."

Miss this EVERY DAY! #4Kforlife #4kportland2012

August 04, 2007

IOCCC Korn 1987

The IOCCC (International Obfuscated C Code Contest) is a yearly competition to write clever or underhanded C code. David Korn's 1987 one-liner is one of my favorite IOCCC entries for its density.

main() { printf(&unix["\021%six\012\0"],(unix)["have"]+"fun"-0x60);}

When run, this one-liner prints the string "unix".

Understanding this one-liner hinges on understanding that a[i] = i[a] in C; this is because both are *(a + i) and addition is commutative.

The mysterious "unix" appearing twice here is a traditional macro, defined on UNIX systems; In modern code, it has been surpassed by __unix__. It is directing the printf to start at the first (not zeroth) character of the string. The \021 and \012 are octal - the \021 is placed in here for trickery and deceit, which the \012 is the same is \n.

Lets simplify, so that printf is just printing a string and a newline:

main() { printf("%six \n",(unix)["have"]+"fun"-0x60);}

Now, the second part is trickier - we have (unix)["have"], which is the first (not zeroth) character of the string "have", which is 'a'. We are then adding this character to the string "fun" and subtracting 0x60.

The trick is that the character 'a' is 0x61; subtracting 0x60 leaves us with the string 1 + "fun". And now the magic - in C, the string literal functions as a pointer. "fun" + 1 is "un".

This whole line is the same as:

main() { printf("%six \n", "un");}

It should now be clear why this program prints "unix".